Himalayas Mountains On A Map

| Himalayas | |

|---|---|

The arc of the Himalayas (also Hindu Kush and Karakorams) showing the viii-thousanders (in crimson); Indo-Gangetic Plain; Tibetan plateau; rivers Indus, Ganges, and Yarlung Tsangpo-Brahmaputra; and the two anchors of the range (in yellow) | |

| Highest bespeak | |

| Elevation | Mountain Everest, Mainland china and Nepal |

| Pinnacle | viii,848.86 g (29,031.vii ft) |

| Coordinates | 27°59′N 86°55′E / 27.983°Northward 86.917°Eastward / 27.983; 86.917 Coordinates: 27°59′Due north 86°55′Due east / 27.983°North 86.917°E / 27.983; 86.917 |

| Dimensions | |

| Length | two,400 km (1,500 mi) |

| Naming | |

| Native name | Himālaya (Sanskrit) |

| Geography | |

| Mount Everest and surrounding peaks as seen from the north-northwest over the Tibetan Plateau. Four eight-thousanders tin be seen, Makalu (viii,462 grand), Everest (8,848 thou), Kanchenjunga (viii,586 m), and Lhotse (8,516 grand). | |

| Countries | Bhutan, Communist china, India, Nepal and Pakistan. Sovereignty in the Kashmir region is disputed past Cathay, India, and Pakistan. |

| Continent | Asia |

| Geology | |

| Orogeny | Tall orogeny |

| Age of rock | Cretaceous-to-Cenozoic |

| Type of rock | Metamorphic, sedimentary |

The Himalayas, or Himalaya (; Sanskrit: [ɦɪmaːlɐjɐ]; from Sanskrit himá 'snow, frost', and ā-laya 'dwelling, dwelling'),[1] is a mount range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the planet's highest peaks, including the very highest, Mountain Everest. Over 100 peaks exceeding 7,200 m (23,600 ft) in elevation lie in the Himalayas. By contrast, the highest peak exterior Asia (Aconcagua, in the Andes) is 6,961 thou (22,838 ft) tall.[2]

The Himalayas adjoin or cross five countries: Kingdom of bhutan, India, Nepal, Cathay, and Pakistan. The sovereignty of the range in the Kashmir region is disputed amidst India, Pakistan, and Communist china.[three] The Himalayan range is bordered on the northwest by the Karakoram and Hindu Kush ranges, on the north past the Tibetan Plateau, and on the south by the Indo-Gangetic Patently. Some of the world's major rivers, the Indus, the Ganges, and the Tsangpo–Brahmaputra, rise in the vicinity of the Himalayas, and their combined drainage bowl is abode to some 600 meg people; 53 one thousand thousand people live in the Himalayas.[4] The Himalayas accept profoundly shaped the cultures of South Asia and Tibet. Many Himalayan peaks are sacred in Hinduism and Buddhism; the summits of several—Kangchenjunga (from the Indian side), Gangkhar Puensum, Machapuchare, Nanda Devi and Kailas in the Tibetan Transhimalaya—are off-limits to climbers.

Lifted by the subduction of the Indian tectonic plate nether the Eurasian Plate, the Himalayan mount range runs due west-northwest to east-southeast in an arc 2,400 km (1,500 mi) long.[5] Its western anchor, Nanga Parbat, lies merely south of the northernmost bend of the Indus river. Its eastern anchor, Namcha Barwa, lies immediately westward of the slap-up bend of the Yarlung Tsangpo River. The range varies in width from 350 km (220 mi) in the westward to 150 km (93 mi) in the due east.[half dozen]

Proper noun [edit]

The name of the range hails from the Sanskrit Himālaya (हिमालय 'dwelling house of the snow'[7]), from himá (हिम 'snow'[8]) and ā-laya (आलय 'home, home'[nine]).[x] [11] They are now known every bit "the Himalaya Mountains", usually shortened to "the Himalayas".

The mountains are known as the Himālaya in Nepali and Hindi (both written हिमालय ), Himāl (हिमाल) in Kumaoni, the Himalaya ( ཧི་མ་ལ་ཡ་ ) or 'The Land of Snowfall' ( གངས་ཅན་ལྗོངས་ ) in Tibetan, also known every bit Himālaya in Sinhala written as හිමාලය , the Himāliya Mountain Range ( سلسلہ کوہ ہمالیہ ) in Urdu, the Himaloy Parvatmala ( হিমালয় পর্বতমালা ) in Bengali and the Ximalaya Mount Range (simplified Chinese: 喜马拉雅山脉; traditional Chinese: 喜馬拉雅山脉; pinyin: Xǐmǎlāyǎ Shānmài ) in Chinese.

The proper noun of the range is sometimes also given as Himavan in older writings, including the Sanskrit epic Mahabharata.[12] Himavat (Sanskrit: हिमवत्) or Himavan Himavān (Sanskrit: हिमवान्) is a Hindu deity who is the personification of the Himalayan Mountain Range. Other epithets include Himaraja (Sanskrit: हिमराज, lit. king of snow) or Parvateshwara (Sanskrit: पर्वतेश्वर, lit. lord of mountains).

In western literature, some writers refer to it as the Himalaya. This was also previously transcribed every bit Himmaleh, as in Emily Dickinson's verse[thirteen] and Henry David Thoreau'due south essays.[14]

History [edit]

The vast mountain range that forms the Himalayas emerged effectually 47 meg years ago when the first oceanic microplate formed the Indian and Eurasian plates. Buddhism arose in the 6th century BCE and long after the death of Gautama Buddha, it arrived in the Himalayas in the seventh-8th century.

The Himalayas soon became a pioneering trek for mountaineers, including Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay who became the first men to climb Mount Everest in 1953.

Geography and central features [edit]

The Himalayas consist of parallel mountain ranges: the Sivalik Hills on the south; the Lower Himalayan Range; the Not bad Himalayas, which is the highest and central range; and the Tibetan Himalayas on the north.[15] The Karakoram are mostly considered separate from the Himalayas.

In the eye of the great curve of the Himalayan mountains lie the 8,000 m (26,000 ft) peaks of Dhaulagiri and Annapurna in Nepal, separated by the Kali Gandaki Gorge. The gorge splits the Himalayas into Western and Eastern sections both ecologically and orographically – the pass at the head of the Kali Gandaki the Kora La is the lowest point on the ridgeline between Everest and K2 (the highest peak of the Karakoram range). To the eastward of Annapurna are the 8,000 grand (five.0 mi) peaks of Manaslu and across the edge in Tibet, Shishapangma. To the south of these lies Kathmandu, the capital of Nepal and the largest urban center in the Himalayas. East of the Kathmandu Valley lies the valley of the Bhote/Sun Kosi river which rises in Tibet and provides the main overland route between Nepal and China – the Araniko Highway/China National Highway 318. Further east is the Mahalangur Himal with four of the world'south half dozen highest mountains, including the highest: Cho Oyu, Everest, Lhotse and Makalu. The Khumbu region, popular for trekking, is found here on the southward-western approaches to Everest. The Arun river drains the northern slopes of these mountains, before turning south and flowing to the range to the east of Makalu.

In the far east of Nepal, the Himalayas rise to the Kangchenjunga massif on the border with India, the third highest mountain in the world, the most easterly 8,000 k (26,000 ft) superlative and the highest point of Bharat. The eastern side of Kangchenjunga is in the Indian country of Sikkim. Formerly an contained Kingdom, information technology lies on the main route from India to Lhasa, Tibet, which passes over the Nathu La laissez passer into Tibet. East of Sikkim lies the ancient Buddhist Kingdom of Kingdom of bhutan. The highest mount in Bhutan is Gangkhar Puensum, which is also a potent candidate for the highest unclimbed mountain in the world. The Himalayas hither are becoming increasingly rugged with heavily forested steep valleys. The Himalayas go along, turning slightly northeast, through the Indian State of Arunachal Pradesh too as Tibet, before reaching their easterly conclusion in the peak of Namche Barwa, situated in Tibet within the bully bend of the Yarlang Tsangpo river. On the other side of the Tsangpo, to the east, are the Kangri Garpo mountains. The high mountains to the north of the Tsangpo including Gyala Peri, however, are besides sometimes included in the Himalayas.

Going west from Dhaulagiri, Western Nepal is somewhat remote and lacks major high mountains, just is home to Rara Lake, the largest lake in Nepal. The Karnali River rises in Tibet simply cuts through the centre of the region. Further due west, the border with Bharat follows the Sarda River and provides a trade route into China, where on the Tibetan plateau lies the high peak of Gurla Mandhata. Just across Lake Manasarovar from this lies the sacred Mountain Kailash in the Kailash Ranges, which stands close to the source of the four main rivers of Himalayas and is revered in Hinduism, Buddhism, Sufism, Jainism, and Bonpo. In Uttarakhand, the Himalayas ascension again as the Kumaon and Garhwal Himalayas[16] with the high peaks of Nanda Devi and Kamet. The state is also home to the of import pilgrimage destinations of Chaar Dhaam, with Gangotri, the source of the holy river Ganges, Yamunotri, the source of the river Yamuna, and the temples at Badrinath and Kedarnath. Uttarakhand Himalayas are regionally divided into two, namely, Kumaon hills in Kumaon division and Garhwal hills in Garhwal sectionalization.[17]

The adjacent Himalayan Indian country, Himachal Pradesh, is noted for its hill stations, particularly Shimla, the summer capital of the British Raj, and Dharamsala, the centre of the Tibetan community and regime in exile in India. This expanse marks the outset of the Punjab Himalaya and the Sutlej river, the most easterly of the five tributaries of the Indus, cuts through the range here. Further w, the Himalayas form much of the disputed Indian-administered marriage territory of Jammu and Kashmir where lies the renowned Kashmir Valley and the boondocks and lakes of Srinagar. The Himalayas form nearly of the south-west portion of the disputed Indian-administered wedlock territory of Ladakh. The twin peaks of Nun Kun are the only mountains over 7,000 m (4.3 mi) in this part of the Himalayas. Finally, the Himalayas reach their western stop in the dramatic 8000 m peak of Nanga Parbat, which rises over viii,000 m (26,000 ft) above the Indus valley and is the most westerly of the 8000 m summits. The western end terminates at a magnificent point near Nanga Parbat where the Himalayas intersect with the Karakoram and Hindu Kush ranges, in the disputed Pakistani-administered territory of Gilgit-Baltistan. Some portion of the Himalayas, such as the Kaghan Valley, Margalla Hills and Galyat tract, extend into the Pakistani provinces of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Punjab.

Geology [edit]

The six,000-kilometre-plus (3,700 mi) journey of the Republic of india landmass (Indian Plate) before its collision with Asia (Eurasian Plate) almost 40 to 50 million years ago[xviii]

The Himalayan range is ane of the youngest mountain ranges on the planet and consists generally of uplifted sedimentary and metamorphic rock. According to the modern theory of plate tectonics, its formation is a result of a continental collision or orogeny along the convergent boundary (Chief Himalayan Thrust) between the Indo-Australian Plate and the Eurasian Plate. The Arakan Yoma highlands in Myanmar and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal were likewise formed as a result of this collision.

During the Upper Cretaceous, almost lxx million years ago, the north-moving Indo-Australian Plate (which has subsequently broken into the Indian Plate and the Australian Plate[19]) was moving at about fifteen cm (5.9 in) per year. About l million years ago this fast-moving Indo-Australian Plate had completely airtight the Tethys Ocean, the existence of which has been determined by sedimentary rocks settled on the body of water floor and the volcanoes that fringed its edges. Since both plates were composed of depression density continental chaff, they were thrust faulted and folded into mount ranges rather than subducting into the mantle along an oceanic trench.[xviii] An oftentimes-cited fact used to illustrate this process is that the meridian of Mount Everest is made of marine limestone from this ancient ocean.[xx]

Today, the Indian plate continues to exist driven horizontally at the Tibetan Plateau, which forces the plateau to continue to move upwards.[21] The Indian plate is still moving at 67 mm per yr, and over the next 10 meg years it will travel about one,500 km (930 mi) into Asia. Most 20 mm per year of the India-Asia convergence is absorbed past thrusting along the Himalaya southern front. This leads to the Himalayas rise by about 5 mm per yr, making them geologically active. The movement of the Indian plate into the Asian plate besides makes this region seismically active, leading to earthquakes from fourth dimension to time.

During the last ice age, at that place was a connected water ice stream of glaciers betwixt Kangchenjunga in the east and Nanga Parbat in the west.[22] [23] In the westward, the glaciers joined with the water ice stream network in the Karakoram, and in the north, they joined with the old Tibetan inland ice. To the due south, outflow glaciers came to an end below an height of 1,000–2,000 g (three,300–half-dozen,600 ft).[22] [24] While the electric current valley glaciers of the Himalaya reach at almost 20 to 32 km (12 to 20 mi) in length, several of the main valley glaciers were threescore to 112 km (37 to 70 mi) long during the water ice age.[22] The glacier snowline (the altitude where accumulation and ablation of a glacier are balanced) was most i,400–ane,660 thou (iv,590–5,450 ft) lower than it is today. Thus, the climate was at least 7.0 to 8.3 °C (12.6 to 14.ix °F) colder than information technology is today.[25]

Hydrology [edit]

Despite their scale, the Himalayas do non form a major watershed, and a number of rivers cut through the range, particularly in the eastern part of the range. As a result, the main ridge of the Himalayas is not conspicuously defined, and mountain passes are not as significant for traversing the range as with other mountain ranges. The rivers of the Himalayas bleed into two large river systems:

- The western rivers combine into the Indus Basin. The Indus itself forms the northern and western boundaries of the Himalayas. Information technology begins in Tibet at the confluence of Sengge and Gar rivers and flows north-w through Republic of india into Pakistan earlier turning south-west to the Arabian Ocean. Information technology is fed past several major tributaries draining the southern slopes of the Himalayas, including the Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Beas and Sutlej rivers, the five rivers of the Punjab.

- The other Himalayan rivers bleed the Ganges-Brahmaputra Basin. Its primary rivers are the Ganges, the Brahmaputra and the Yamuna, as well as other tributaries. The Brahmaputra originates every bit the Yarlung Tsangpo River in western Tibet, and flows east through Tibet and west through the plains of Assam. The Ganges and the Brahmaputra run across in Bangladesh and drain into the Bay of Bengal through the world'southward largest river delta, the Sunderbans.[26]

The northern slopes of Gyala Peri and the peaks beyond the Tsangpo, sometimes included in the Himalayas, drain into the Irrawaddy River, which originates in eastern Tibet and flows southward through Myanmar to bleed into the Andaman Sea. The Salween, Mekong, Yangtze and Yellow River all originate from parts of the Tibetan Plateau that are geologically distinct from the Himalaya mountains and are therefore not considered true Himalayan rivers. Some geologists refer to all the rivers collectively as the circum-Himalayan rivers.[27]

Glaciers [edit]

The swell ranges of central Asia, including the Himalayas, contain the tertiary-largest deposit of ice and snow in the world, after Antarctica and the Arctic.[28] The Himalayan range encompasses about 15,000 glaciers, which store about 12,000 km3 (2,900 cu mi) of fresh water.[29] Its glaciers include the Gangotri and Yamunotri (Uttarakhand) and Khumbu glaciers (Mount Everest region), Langtang glacier (Langtang region) and Zemu (Sikkim).

Owing to the mountains' latitude near the Tropic of Cancer, the permanent snow line is amid the highest in the earth at typically effectually five,500 m (18,000 ft).[30] In dissimilarity, equatorial mountains in New Guinea, the Rwenzoris and Republic of colombia have a snow line some 900 k (2,950 ft) lower.[31] The higher regions of the Himalayas are snowbound throughout the year, in spite of their proximity to the torrid zone, and they grade the sources of several large perennial rivers.

In recent years, scientists have monitored a notable increment in the rate of glacier retreat across the region as a result of climate modify.[32] [33] For example, glacial lakes have been forming rapidly on the surface of debris-covered glaciers in the Bhutan Himalaya during the last few decades. Although the issue of this will not be known for many years, it potentially could mean disaster for the hundreds of millions of people who rely on the glaciers to feed the rivers during the dry seasons.[34] [35] [36] The global climatic change will affect the water resources and livelihoods of the Greater Himalayan region.

Lakes [edit]

The Himalayan region is dotted with hundreds of lakes.[37] Pangong Tso, which is spread beyond the border between India and China, at far western end of Tibet, is among the largest with surface areas of 700 kmtwo (270 sq mi).

South of the main range, the lakes are smaller. Tilicho Lake in Nepal in the Annapurna massif is ane of the highest lakes in the world. Other notable lakes include Rara Lake in western Nepal, She-Phoksundo Lake in the Shey Phoksundo National Park of Nepal, Gurudongmar Lake, in North Sikkim, Gokyo Lakes in Solukhumbu district of Nepal and Lake Tsongmo, near the Indo-People's republic of china border in Sikkim.[37]

Some of the lakes nowadays a danger of a glacial lake outburst inundation. The Tsho Rolpa glacier lake in the Rowaling Valley, in the Dolakha District of Nepal, is rated as the most unsafe. The lake, which is located at an altitude of four,580 grand (fifteen,030 ft) has grown considerably over the last 50 years due to glacial melting.[38] [39] The mountain lakes are known to geographers every bit tarns if they are caused by glacial activity. Tarns are found generally in the upper reaches of the Himalaya, above 5,500 m (eighteen,000 ft).[forty]

Temperate Himalayan wetlands provide important habitat and layover sites for migratory birds. Many mid and low altitude lakes remain poorly studied in terms of their hydrology and biodiversity, like Khecheopalri in the Sikkim Eastern Himalayas.[41]

Climate [edit]

Temperature [edit]

The physical factors determining the climate in any location in the Himalayas include breadth, altitude, and the relative motion of the Southwest monsoon.[42] From due south to northward, the mountains encompass more than eight degrees of latitude, spanning temperate to subtropical zones.[42] The colder air of Cardinal Asia is prevented from blowing down into Southward Asia by the physical configuration of the Himalayas.[42] This causes the tropical zone to extend farther due north in Southern asia than anywhere else in the world.[42] The evidence is unmistakable in the Brahmaputra valley as the warm air from the Bay of Bengal bottlenecks and rushes up past Namcha Barwa, the eastern ballast of the Himalayas, and into southeastern Tibet.[42] Temperatures in the Himalayas cool past 2.0 degrees C (three.6 degrees F) for every 300 metres (980 ft) increase of altitude.[42]

As the physical features of mountains are irregular, with cleaved jagged contours, there can be broad variations in temperature over brusque distances.[43] Temperature at a location on a mountain depends on the flavour of the year, the bearing of the sun with respect to the face on which the location lies, and the mass of the mountain, i.e. the amount of thing in the mountain.[43] As the temperature is directly proportional to received radiation from the sun, the faces that receive more direct sunlight also have a greater heat buildup.[43] In narrow valleys—lying betwixt steep mountain faces—there can be dramatically different weather along their two margins.[43] The side to the n with a mountain above facing s can take an extra calendar month of the growing season.[43] The mass of the mountain too influences the temperature, as information technology acts as a heat island, in which more heat is absorbed and retained than the surroundings, and therefore influences the heat budget or the amount of heat needed to raise the temperature from the winter minimum winter to the summer maximum.[43] The immense calibration of the Himalayas ways that many summits tin can create their ain weather condition, the temperature fluctuating from one summit to another, from one face to another, and all may be quite different from the conditions in nearby plateaus or valleys.[43]

Precipitation [edit]

A critical influence on the Himalayan climate is the Southwest Monsoon. This is not so much the rain of the summer months as the air current that carries the pelting.[43] Unlike rates of heating and cooling between the Primal Asian continent and the S Asian bounding main create large differences in the atmospheric pressure prevailing above each.[43] In the winter, a high-force per unit area arrangement forms and remains suspended above Central Asia, forcing air to flow in the southerly direction over the Himalayas.[43] Just in Fundamental Asia as there is no substantial source for water to be diffused as vapour, the winter winds blowing across South Asia are dry.[43] In the summer months the Fundamental Asian plateau heats upward more than the body of water waters to its south. As a result, the air above it rises higher and higher, creating a zone of depression pressure.[43] Off-shore high-pressure level systems in the Indian ocean push the moist summer air inland toward the low-force per unit area system. When the moist air meets mountains, information technology rises and upon subsequent cooling, its moisture condenses and is released as pelting, typically heavy rain.[43] The moisture summer monsoon winds cause precipitation in India and all along the layered southern slopes of the Himalayas. This forced lifting of air is called the orographic effect.[43]

Winds [edit]

The vast size, huge altitude range, and circuitous topography of the Himalayas mean they experience a broad range of climates, from boiling subtropical in the foothills to common cold and dry out desert conditions on the Tibetan side of the range. For much of the Himalayas—in the areas to the south of the loftier mountains, the monsoon is the most characteristic feature of the climate and causes nearly of the atmospheric precipitation, while the western disturbance brings winter precipitation, especially in the west. Heavy rain arrives on the southwest monsoon in June and persists until September. The monsoon can seriously impact send and cause major landslides. Information technology restricts tourism – the trekking and mountaineering flavour is limited to either before the monsoon in Apr/May or after the monsoon in Oct/November (autumn). In Nepal and Sikkim, there are often considered to be five seasons: summer, monsoon, fall, (or post-monsoon), winter, and bound.

Using the Köppen climate nomenclature, the lower elevations of the Himalayas, reaching in mid-elevations in central Nepal (including the Kathmandu valley), are classified as Cwa, Boiling subtropical climate with dry winters. Above, most of the Himalayas have a subtropical highland climate (Cwb).

The intensity of the southwest monsoon diminishes every bit it moves w along the range, with as much as ii,030 mm (fourscore in) of rainfall in the monsoon season in Darjeeling in the eastward, compared to but 975 mm (38.4 in) during the same period in Shimla in the west.[44] [45]

The northern side of the Himalayas, besides known as the Tibetan Himalaya, is dry out, cold and, generally, windswept particularly in the west where information technology has a cold desert climate. The vegetation is sparse and stunted and the winters are severely cold. Almost of the precipitation in the region is in the form of snow during the belatedly winter and spring months.

Local impacts on climate are significant throughout the Himalayas. Temperatures fall past 0.two to 1.2 °C for every 100 chiliad (330 ft) rising in altitude.[46] This gives rise to a variety of climates from a almost tropical climate in the foothills, to tundra and permanent snow and ice at higher elevations. Local climate is as well affected by the topography: The leeward side of the mountains receive less pelting while the well exposed slopes get heavy rainfall and the pelting shadow of big mountains can be significant, for example leading to near desert atmospheric condition in the Upper Mustang which is sheltered from the monsoon rains by the Annapurna and Dhaulagiri massifs and has annual precipitation of around 300 mm (12 in), while Pokhara on the southern side of the massifs has substantial rainfall (3,900 mm or 150 in a year). Thus although annual precipitation is generally higher in east than the west, local variations are often more important.

The Himalayas accept a profound effect on the climate of the Indian subcontinent and the Tibetan Plateau. They prevent frigid, dry out winds from blowing south into the subcontinent, which keeps South Asia much warmer than corresponding temperate regions in the other continents. Information technology also forms a barrier for the monsoon winds, keeping them from traveling northwards, and causing heavy rainfall in the Terai region. The Himalayas are besides believed to play an important part in the germination of Central Asian deserts, such as the Taklamakan and Gobi.[47]

Climatic change [edit]

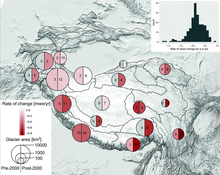

Observed glacier mass loss in the HKH since the 20th century.

The 2019 Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment[48] concluded that betwixt 1901 to 2014, the Hindu Kush Himalaya (or HKH) region had already experienced warming of 0.1 °C per decade, with the warming rate accelerating to 0.two °C per decade over the past 50 years.Over the past 50 years, the frequency of warm days and nights had likewise increased by 1.2 days and 1.vii nights per decade, while the frequency of extreme warm days and nights had increased past 1.26 days and 2.54 nights per decade. At that place was also a corresponding decline of 0.five cold days, 0.85 extreme cold days, i cold night, and 2.4 extreme cold nights per decade. The length of the growing season has increased by 4.25 days per decade. In that location is less conclusive prove of calorie-free atmospheric precipitation becoming less frequent while heavy atmospheric precipitation became both more frequent and more intense. Finally, since 1970s glaciers have retreated everywhere in the region abreast Karakoram, eastern Pamir, and western Kunlun, where there has been an unexpected increase in snowfall. Glacier retreat had been followed past an increase in the number of glacial lakes, some of which may exist prone to unsafe floods.[49]

In the hereafter, if the Paris Agreement goal of 1.v °C of global warming is not exceeded, warming in the HKH volition be at least 0.3 °C higher, and at least 0.7 °C higher in the hotspots of northwest Himalaya and Karakoram. If the Paris Agreement goals are broken, so the region is expected to warm by i.7–2.4 °C in the near time to come (2036–2065) and by 2.two–3.3 °C (2066–2095) near the end of the century nether the "intermediate" Representative Concentration Pathway 4.five (RCP4.5). Under the high-warming RCP8.5 scenario where the annual emissions continue to increase for the residue of the century, the expected regional warming is 2.three–three.2 °C and four.2–6.5 °C, respectively. Under all scenarios, winters will warm more the summers, and the Tibetan Plateau, the central Himalayan Range, and the Karakoram will continue to warm more than the rest of the region. Climate change volition also lead to the degradation of up to 81% of the region's permafrost by the cease of the century.[49]

Hereafter atmospheric precipitation is projected to increase equally well, but CMIP5 models struggle to make specific projections due to the region'southward topography: the about certain finding is that the monsoon precipitation in the region volition increase by 4–12% in the near futurity and by iv–25% in the long term.[49] There has also been modelling of the changes in snow cover, but it is limited to the end of century under the RCP viii.5 scenario: it projects declines of 30–50% in the Indus Basin, 50–60% in the Ganges basin, and 50–70% in the Brahmaputra Basin, as the snowline elevation in these regions will rise by between four.four and 10.0 m/yr. There has been more extensive modelling of glacier trends: it is projected that ane tertiary of all glaciers in the extended HKH region volition exist lost by 2100 fifty-fifty if the warming is express to 1.5 °C (with over one-half of that loss in the Eastern Himalaya region), while RCP 4.5 and RCP viii.5 are likely to lead to the losses of fifty% and >67% of the region's glaciers over the same timeframe. Glacier melt is projected to accelerate regional river flows until the amount of meltwater peaks effectually 2060, going into an irreversible turn down afterwards. Since precipitation will continue to increment even every bit the glacier meltwater contribution declines, almanac river flows are only expected to diminish in the western basins where contribution from the monsoon is low: even so, irrigation and hydropower generation would still take to adjust to greater interannual variability and lower pre-monsoon flows in all of the region's rivers.[50] [51] [52]

Environmental [edit]

The flora and brute of the Himalayas vary with climate, rainfall, altitude, and soils. The climate ranges from tropical at the base of the mountains to permanent ice and snowfall at the highest elevations. The amount of yearly rainfall increases from due west to due east along the southern front end of the range. This variety of altitude, rainfall, and soil weather combined with the very high snow line supports a variety of distinct plant and beast communities.[37] The extremes of high altitude (depression atmospheric pressure) combined with extreme cold favor extremophile organisms.[53] [41]

At high altitudes, the elusive and previously endangered snow leopard is the main predator. Its prey includes members of the caprine animal family grazing on the alpine pastures and living on the rocky terrain, notably the owned bharal or Himalayan blue sheep. The Himalayan musk deer is also plant at high altitudes. Hunted for its musk, it is at present rare and endangered. Other endemic or almost-endemic herbivores include the Himalayan tahr, the takin, the Himalayan serow, and the Himalayan goral. The critically endangered Himalayan subspecies of the brownish comport is institute sporadically across the range as is the Asian black bear. In the mountainous mixed deciduous and conifer forests of the eastern Himalayas, Red panda feed in the dense understories of bamboo. Lower down the forests of the foothills are inhabited by several different primates, including the endangered Gee'south golden langur and the Kashmir grey langur, with highly restricted ranges in the e and west of the Himalayas respectively.[41]

The unique floral and faunal wealth of the Himalayas is undergoing structural and compositional changes due to climate change. Hydrangea hirta is an case of floral species that tin be found in this area. The increment in temperature is shifting diverse species to higher elevations. The oak wood is being invaded by pino forests in the Garhwal Himalayan region. At that place are reports of early flowering and fruiting in some tree species, especially rhododendron, apple and box myrtle. The highest known tree species in the Himalayas is Juniperus tibetica located at 4,900 1000 (16,080 ft) in Southeastern Tibet.[54]

The mountainous areas of Hindu Kush range are mostly barren or at the most sparsely sprinkled with copse and stunted bushes. From about 1,300 to 2,300 m (four,300 to 7,500 ft), states Yarshater, "sclerophyllous forests are predominant with Quercus and Olea (wild olive); higher up that, up to a acme of virtually 3,300 m (x,800 ft) ane finds coniferous forests with Cedrus, Picea, Abies, Pinus, and junipers". The inner valleys of the Hindu Kush run across little pelting and accept desert vegetation.[55] On the other hand, Eastern Himalaya is home to multiple biodiversity hotspots, and 353 new species (242 plants, sixteen amphibians, 16 reptiles, 14 fish, two birds, two mammals and 61+ invertebrates) have been discovered there in betwixt 1998 and 2008, with an boilerplate of 35 new species finds every yr. With Eastern Himalaya included, the entire Hindu Kush Himalaya region is home to an estimated 35,000+ species of plants and 200+ species of animals.[48]

Religions [edit]

There are many cultural and mythological aspects associated with the Himalayas. In Jainism, Mountain Ashtapad of the Himalayan mountain range, is a sacred place where the commencement Jain Tirthankara, Rishabhdeva attained moksha. It is believed that afterwards Rishabhdeva attained nirvana, his son, Emperor Bharata Chakravartin, had constructed three stupas and twenty four shrines of the 24 Tirthankaras with their idols studded with precious stones over there and named it Sinhnishdha.[56] [57] [58] For the Hindus, the Himalayas are personified as Himavat, rex of all mountains and the father of the goddess Parvati.[59] The Himalayas are likewise considered to be the father of Ganga (the personification of river Ganges).[60] Two of the most sacred places of pilgrimage for the Hindus are the temple complex in Pashupatinath and Muktinath, also known as Saligrama because of the presence of the sacred blackness rocks called saligrams.[61]

The Buddhists also lay a groovy deal of importance on the Himalayas. Paro Taktsang is the holy place where Buddhism started in Bhutan.[62] The Muktinath is also a identify of pilgrimage for the Tibetan Buddhists. They believe that the trees in the poplar grove came from the walking sticks of fourscore-iv ancient Indian Buddhist magicians or mahasiddhas. They consider the saligrams to be representatives of the Tibetan snake deity known every bit Gawo Jagpa.[63] The Himalayan people'southward diversity shows in many dissimilar means. It shows through their compages, their languages, and dialects, their beliefs and rituals, as well equally their clothing.[63] The shapes and materials of the people'due south homes reverberate their practical needs and beliefs. Another case of the diverseness amongst the Himalayan peoples is that handwoven textiles display colors and patterns unique to their indigenous backgrounds. Finally, some people identify great importance on jewelry. The Rai and Limbu women wear big gold earrings and olfactory organ rings to testify their wealth through their jewelry.[63] Several places in the Himalayas are of religious significance in Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism. A notable example of a religious site is Paro Taktsang, where Padmasambhava is said to accept founded Buddhism in Kingdom of bhutan.[64]

A number of Vajrayana Buddhist sites are situated in the Himalayas, in Tibet, Bhutan and in the Indian regions of Ladakh, Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh, Spiti and Darjeeling. At that place were over half-dozen,000 monasteries in Tibet, including the residence of the Dalai Lama.[65] Bhutan, Sikkim and Ladakh are too dotted with numerous monasteries.

Resources [edit]

The Himalayas are home to a diversity of medicinal resources. Plants from the forests have been used for millennia to care for conditions ranging from simple coughs to snake bites.[61] Different parts of the plants – root, blossom, stem, leaves, and bawl – are used as remedies for different ailments. For example, a bawl excerpt from an Abies pindrow tree is used to treat coughs and bronchitis. Leaf and stalk paste from an Andrachne cordifolia is used for wounds and as an antidote for snake bites. The bawl of a Callicarpa arborea is used for skin ailments.[61] Nearly a 5th of the gymnosperms, angiosperms and pteridophytes in the Himalayas are constitute to have medicinal properties, and more than are probable to be discovered.[61]

Most of the population in some Asian and African countries depends on medicinal plants rather than prescriptions and such.[59] Since and so many people utilise medicinal plants as their only source of healing in the Himalayas, the plants are an of import source of income. This contributes to economic and mod industrial evolution both inside and outside the region.[59] The only problem is that locals are apace clearing the forests on the Himalayas for wood, often illegally.[66]

Future Development and climate change adaptation [edit]

A range of adaptation efforts are already undertaken across the HKH region: however, they endure from underinvestment and insufficient coordination betwixt the various state, institutional and other non-land efforts, and need to be "urgently" strengthened in order to be commensurate with the challenges alee.[67]

The 2019 Hindu Kush Himalaya Cess outlined three main "storylines" for the region betwixt now and 2080: "business organisation-as-usual" (or "muddling through"), with no significant change from the current trends and development/adaptation initiatives proceeding every bit they do now; "downhill", where the intensity of global climate alter is high, local initiatives fail and regional cooperation breaks down; and "prosperous", where extensive cooperation allows region's communities to weather "moderate" climate change and increase their living standards while too preserving the region'due south biodiversity. In addition, it described ii alternate pathways through which the "prosperous" future can be achieved: the first focuses on summit-down, large-scale evolution and the latter describes a bottom-upward, decentralized alternative.[68]

| Actions | Benefits | Need | Risk | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic | Social | Environmental/climate | Cross sectoral | Finance and human resources | Governance | Source | |

| Large hydro ability generating chapters | Leapfrog in economic prosperity for the region as a whole, high potential for power trade | New skill development, diversified livelihood options | Air pollution reduction, both accommodation and mitigation | Large h2o storage to manage seasonal variability and strategic cross-sector allocation | Large corporate, global finance, sustained climate finance | HKH establishment, regional tariff, cross-border policy coordination | Lack of transboundary sustainable political cooperation; lack of cantankerous-sector water sharing formal arrangements; lack of ecosystem-based pattern of reservoirs/power plants; public acceptance, silt accumulation |

| HKH and non-HKH electric grid | Very high economical prosperity for the region and beyond | New skill, non-farm diversified livelihood options | Unplanned local resource extraction will decrease | Reliable ability supply for all sectors | Large corporate, global finance, climate finance | HKH electric distribution corporation | Transboundary sustainable political cooperation;lack of ecosystem-based design |

| HKH ICT (information and communications technology) network | Boost to regional and local economic growth | New skill, not-farm diversified livelihood options | Connectivity across mountainous terrain without ecological bear on | Extent of market cutting across sectors and regions | Large corporations, global finance, climate finance | HKH communications corporation | Transboundary sustainable political cooperation; lack of biodiversity-sensitive design |

| Cross-edge trade corridors e.g., silk route re-development | Income, consumption, production leapfrogs as per comparative advantage, benefit to large-calibration tourism industry | Food security, energy security, health service, social interdependence, non-subcontract livelihood generation | Comparative reward will lead to biodiversity conservation, enhance payment for ecosystem service | Multiple opportunities across sectors emerge | Regional, global | HKH trade authority | Transboundary sustainable political cooperation; lack of biodiversity-sensitive design in transport corridor development |

| Large water storage and supply | Income, consumption, product leapfrog | Nutrient security, energy security, non-farm h2o sector livelihood generation | Less GLOF, less flash floods, pump storage facility | Multiple opportunities across sectors emerge | Regional, global | HKH h2o council | Transboundary sustainable political cooperation; lack of ecosystem-sensitive evolution |

| Large water treatment facilities | Leapfrog in water resource management | Water security, non-farm water sector livelihood generation | Reduction in waste disposal | Multiple opportunities across sectors emerge | Regional, global | HKH water council | Transboundary sustainable political cooperation; lack of ecosystem sensitive evolution |

| Large-scale urbanization | Leapfrog in economic growth centers | Not-subcontract water sector livelihood generation | Reserve nature for biodiversity conservation | Multiple opportunities across sectors emerge | Local, national, regional, and global | National urban development authorities | Lack of ecosystem-sensitive development |

| Large contract farming | Leapfrog in farm-level action and income | Income, livelihood security | Investment in environmental management | Farming based industrial/trade growth | Local, national, regional, and global | National farming development regime | Lack of ecosystem-sensitive development; lack of public acceptance, possibility of food crop reduction, ingather monoculture |

| Deportment | Benefits | Need | Take a chance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic | Social | Environmental/climate | Cantankerous sectoral | Finance and human resources | Governance | Source | |

| Distributed small hydro ability generating capacity | Incremental national, local economical prosperity through self-sufficiency | Traditional skill utilization | Air pollution reduction, both adaptation and mitigation | H2o flow uninterrupted | Modest to medium national scale finance, programmatic finance by bundling, climate finance | Community level, local, national, multilevel coordination for tariff, etc. to ensure equity | Lack of local capacity for multi-level governance; lack of upstream- downstream water sharing arrangements; lack of ecosystem-based pattern |

| Micro grids | Local economic prosperity | Lack of ecosystem-sensitive development | Modest infrastructure with less environmental impact | Reliable power supply for target grouping | Specialized medium-calibration global finance, climate finance | Individual, local electrical distribution companies | Without multilevel governance, inequality may ascend across social groups; not a tried and tested engineering science; maintenance will need local skill building |

| National ICT (information and communications engineering science) network | Incremental national growth | Lack of ecosystem-sensitive development | National connectivity in mountainous terrain improves without ecological touch on | Extent of market place cutting across sectors | National/global investment negotiated competitively | National institutions | Lack of local/national skill, national negotiation capacity |

| National culture based products, tourism | Incremental progress | Traditional skill, not-farm livelihood | Environmental conservation | Tourism related infrastructure expansion | Local, national | Local and national institutions | Lack of capacity to integrate with the rest of the world |

| Decentralized water storage and supply | Incremental progress | Traditional systems to be revived | Environmental conservation | Local infrastructure expansion | Local, national | Local, national | New modern engineering science to be developed; lack of local/national skill |

| Decentralized h2o treatment | Incremental Progress | Traditional systems to exist revived | Ecology conservation | Local infrastructure expansion | Local, national | Local, national | New modern engineering science to be adult; lack of local/national skill |

| Modest settlement planning | Less displacement cost | Less deportation and migration | No modify in large-scale land use pattern | Local infrastructure expansion | Local, national | Local, national regulations | Localized ecology affect might go unregulated |

| Pocket-size farming practices | Incremental progress | Continuation of traditional practices | No change in big-scale land utilise pattern | Local infrastructure expansion | Local, national | Local, national regulations | Localized environmental impact might become unregulated |

Come across also [edit]

- Eastern and Western Himalaya

- Indian Himalayan Region

- List of Himalayan peaks and passes

- List of Himalayan topics

- List of mountains in India, Islamic republic of pakistan, Kingdom of bhutan, Nepal and China

- Listing of Ultras of the Himalayas

- Trekking peak

References [edit]

- ^ "Himalayan". Oxford English language Lexicon (Online ed.). Oxford University Printing. Retrieved five August 2021.

Etymology: < Himālaya (Sanskrit < hima snow + ālaya dwelling, abode) + -an suffix)

(Subscription or participating institution membership required.) - ^ Yang, Qinye; Zheng, Du (2004). Himalayan Mountain System. ISBN978-7-5085-0665-4 . Retrieved xxx July 2016.

- ^ Bishop, Barry. "Himalayas (mountains, Asia)". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved xxx July 2016.

- ^ A.P. Dimri; B. Bookhagen; 1000. Stoffel; T. Yasunari (8 November 2019). Himalayan Weather and Climate and their Impact on the Environment. Springer Nature. p. 380. ISBN978-3-030-29684-1.

- ^ Wadia, D. Due north. (1931). "The syntaxis of the northwest Himalaya: its rocks, tectonics and orogeny". Record Geol. Survey of India. 65 (2): 189–220.

- ^ Apollo, M. (2017). "Chapter 9: The population of Himalayan regions – by the numbers: Past, present and hereafter". In Efe, R.; Öztürk, M. (eds.). Contemporary Studies in Surroundings and Tourism. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 143–159.

- ^ "MW Cologne Scan". www.sanskrit-lexicon.uni-koeln.de . Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ^ "MW Cologne Browse". www.sanskrit-dictionary.uni-koeln.de . Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ^ "WIL Cologne Scan". www.sanskrit-lexicon.uni-koeln.de . Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ^ "BEN Cologne Scan". www.sanskrit-lexicon.uni-koeln.de . Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ^ "WIL Cologne Scan". www.sanskrit-lexicon.uni-koeln.de . Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ^ Roshen Dalal (2014). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books. ISBN9788184752779. Entry: "Himavan"

- ^ Dickinson, Emily, The Himmaleh was known to stoop .

- ^ Thoreau, Henry David (1849), A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers .

- ^ Himalayas. Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ "Kumaun Himalayas - mountains, India".

- ^ "Division of the Himalayas: Regional Division of the Himalayas on the Footing of River Valleys". 21 November 2013.

- ^ a b "The Himalayas: Two continents collide". USGS. 5 May 1999. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ "(1995) Geologists Find: An World Plate Is Breaking in Two".

- ^ Mountain Everest – Overview and Data by Matt Rosenberg. ThoughtCo Updated 17 March 2017

- ^ "Plate Tectonics -The Himalayas". The Geological Social club. Retrieved thirteen September 2016.

- ^ a b c Kuhle, Chiliad. (2011). "The High Glacial (Last Ice Age and Concluding Glacial Maximum) Ice Embrace of High and Central Asia, with a Critical Review of Some Recent OSL and TCN Dates". In Ehlers, J.; Gibbard, P.Fifty.; Hughes, P.D. (eds.). Fourth Glaciation – Extent and Chronology, A Closer Look. Amsterdam: Elsevier BV. pp. 943–965.

- ^ glacier maps downloadable

- ^ Kuhle, M. (1987). "Subtropical mountain- and highland-glaciation as ice age triggers and the waning of the glacial periods in the Pleistocene". GeoJournal. 14 (4): 393–421. doi:10.1007/BF02602717. S2CID 129366521.

- ^ Kuhle, M. (2005). "The maximum Ice Age (Würmian, Last Water ice Age, LGM) glaciation of the Himalaya – a glaciogeomorphological investigation of glacier trim-lines, ice thicknesses and lowest former ice margin positions in the Mt. Everest-Makalu-Cho Oyu massifs (Khumbu- and Khumbakarna Himal) including information on late-glacial-, neoglacial-, and historical glacier stages, their snowfall-line depressions and ages". GeoJournal. 62 (3–4): 193–650. doi:10.1007/s10708-005-2338-6.

- ^ "Sunderbans the world's largest delta". gits4u.com. Archived from the original on 3 January 2015. Retrieved iii January 2015.

- ^ Gaillardet, J.; Métivier, F.; Lemarchand, D.; Dupré, B.; Allègre, C.J.; Li, Westward.; Zhao, J. (2003). "Geochemistry of the Suspended Sediments of Circum-Himalayan Rivers and Weathering Budgets over the Concluding 50 Myrs" (PDF). Geophysical Research Abstracts. 5: thirteen,617. Bibcode:2003EAEJA....13617G. Abstract 13617. Archived (PDF) from the original on ix October 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2006.

- ^ "The Himalayas – Himalayas Facts". Nature on PBS. 11 February 2011. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ^ "the Himalayan Glaciers". Fourth assessment report on climate change. IPPC. 2007. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ^ Shi, Yafeng; Xie, Zizhu; Zheng, Benxing; Li, Qichun (1978). "Distribution, Feature and Variations of Glaciers in China" (PDF). World Glacier Inventory. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 Apr 2013.

- ^ Henderson-Sellers, Ann; McGuffie, Kendal (2012). The Hereafter of the World'due south Climate: A Modelling Perspective. pp. 199–201. ISBN978-0-12-386917-3.

- ^ Lee, Ethan; Carrivick, Jonathan Fifty.; Quincey, Duncan J.; Melt, Simon J.; James, William H. M.; Brown, Lee E. (20 December 2021). "Accelerated mass loss of Himalayan glaciers since the Little Ice Age". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 24284. Bibcode:2021NatSR..1124284L. doi:ten.1038/s41598-021-03805-8. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC8688493. PMID 34931039.

- ^ "Vanishing Himalayan Glaciers Threaten a Billion". Reuters. 4 June 2007. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ Kaushik, Saurabh; Rafiq, Mohammd; Joshi, P.K.; Singh, Tejpal (April 2020). "Examining the glacial lake dynamics in a warming climate and GLOF modelling in parts of Chandra basin, Himachal Pradesh, India". Science of the Full Environment. 714: 136455. Bibcode:2020ScTEn.714m6455K. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.136455. PMID 31986382. S2CID 210933887.

- ^ Rafiq, Mohammd; Romshoo, Shakil Ahmad; Mishra, Anoop Kumar; Jalal, Faizan (January 2019). "Modelling Chorabari Lake outburst flood, Kedarnath, India". Periodical of Mountain Science. sixteen (1): 64–76. doi:ten.1007/s11629-018-4972-eight. ISSN 1672-6316. S2CID 134015944.

- ^ "Glaciers melting at alarming speed". People's Daily Online. 24 July 2007. Retrieved 17 Apr 2009.

- ^ a b c O'Neill, A. R. (2019). "Evaluating high-distance Ramsar wetlands in the Sikkim Eastern Himalayas". Global Ecology and Conservation. 20 (e00715): 19. doi:ten.1016/j.gecco.2019.e00715.

- ^ "Photograph of Tsho Rolpa".

- ^ Tsho Rolpa

- ^ Drews, Carl. "Highest Lake in the Globe". Retrieved 14 Nov 2010.

- ^ a b c O'Neill, Alexander; et al. (25 Feb 2020). "Establishing Ecological Baselines Around a Temperate Himalayan Peatland". Wetlands Ecology & Management. 28 (ii): 375–388. doi:10.1007/s11273-020-09710-vii. S2CID 211081106.

- ^ a b c d e f Zurick & Pacheco 2006, p. 50.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j thousand fifty m n Zurick & Pacheco 2006, pp. l–51.

- ^ "Climate of the Himalayas". Encyclopedia Britannica . Retrieved eighteen May 2022.

- ^ Zurick, David; Pocheco, Julsun (2006), Illustrated Atlas of the Himalaya, University Press of Kentucky, p. 52, ISBN9780813173849

- ^ Romshoo, Shakil Ahmad; Rafiq, Mohammd; Rashid, Irfan (March 2018). "Spatio-temporal variation of land surface temperature and temperature lapse rate over mountainous Kashmir Himalaya". Journal of Mountain Scientific discipline. 15 (3): 563–576. doi:x.1007/s11629-017-4566-x. ISSN 1672-6316. S2CID 134568990.

- ^ Devitt, Terry (3 May 2001). "Climate shift linked to rise of Himalayas, Tibetan Plateau". University of Wisconsin–Madison News . Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ^ a b Wester, Philippus; Mishra, Arabinda; Mukherji, Aditi; Shrestha, Arun Bhakta (2019). The Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment: Mountains, Climatic change, Sustainability and People. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-92288-1. ISBN978-iii-319-92288-ane. }}

- ^ a b c Krishnan, Raghavan; Shrestha, Arun Bhakta; Ren, Guoyu; Rajbhandari, Rupak; Saeed, Sajjad; Sanjay, Jayanarayanan; Syed, Md. Abu.; Vellore, Ramesh; Xu, Ying; You, Qinglong; Ren, Yuyu (5 January 2019). "Unravelling Climate Change in the Hindu Kush Himalaya: Rapid Warming in the Mountains and Increasing Extremes". The Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment: Mountains, Climate change, Sustainability and People. pp. 57–97. doi:10.1007/978-three-319-92288-1_3.

- ^ Damian Carrington (iv February 2019). "A third of Himalayan ice cap doomed, finds report". Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ^ Bolch, Tobias; Shea, Joseph M.; Liu, Shiyin; Azam, Farooq M.; Gao, Yang; Gruber, Stephan; Immerzeel, Walter W.; Kulkarni, Anil; Li, Huilin; Tahir, Adnan A.; Zhang, Guoqing; Zhang, Yinsheng (5 January 2019). "Status and Change of the Cryosphere in the Extended Hindu Kush Himalaya Region". The Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment: Mountains, Climatic change, Sustainability and People. pp. 209–255. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-92288-1_7.

- ^ Scott, Christopher A.; Zhang, Fan; Mukherji, Aditi; Immerzeel, Walter; Mustafa, Daanish; Bharati, Luna (5 January 2019). "H2o in the Hindu Kush Himalaya". The Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment: Mountains, Climatic change, Sustainability and People. pp. 257–299. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-92288-1_8.

- ^ Hogan, C. Michael (2010). Monosson, Due east. (ed.). "Extremophile". Encyclopedia of World. Washington, DC: National Council for Scientific discipline and the Surround.

- ^ Miehe, Georg; Miehe, Sabine; Vogel, Jonas; Co, Sonam; Duo, La (May 2007). "Highest Treeline in the Northern Hemisphere Found in Southern Tibet" (PDF). Mount Research and Evolution. 27 (2): 169–173. doi:10.1659/mrd.0792. hdl:1956/2482. S2CID 6061587. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 June 2013.

- ^ Ehsan Yarshater (2003). Encyclopædia Iranica. The Encyclopaedia Iranica Foundation. p. 312. ISBN978-0-933273-76-4.

- ^ Jain, Arun Kumar (2009). Faith & Philosophy of Jainism. ISBN978-81-7835-723-ii.

- ^ "To heaven and back". The Times of India. eleven January 2012. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. Retrieved ii March 2012.

- ^ Jain, Arun Kumar (2009). Faith & Philosophy of Jainism. ISBN978-81-7835-723-2.

- ^ a b c Gupta, Pankaj; Sharma, Vijay Kumar (2014). Healing Traditions of the Northwestern Himalayas. Springer Briefs in Environmental Scientific discipline. ISBN978-81-322-1925-v.

- ^ Dallapiccola, Anna (2002). Dictionary of Hindu Lore and Legend . ISBN978-0-500-51088-ix.

- ^ a b c d Jahangeer A. Bhat; Munesh Kumar; Rainer W. Bussmann (ii January 2013). "Ecological status and traditional knowledge of medicinal plants in Kedarnath Wildlife Sanctuary of Garhwal Himalaya, Bharat". Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. ix: one. doi:ten.1186/1746-4269-9-i. PMC3560114. PMID 23281594.

- ^ Cantor, Kimberly (14 July 2016). "Paro, Bhutan: The Tiger's Nest". Huffington Postal service . Retrieved ix June 2018.

- ^ a b c Zurick, David; Julsun, Pacheco; Basanta, Raj Shrestha; Birendra, Bajracharya (2006). Illustrated Atlas of the Himalaya. Lexington: U of Kentucky.

- ^ Pommaret, Francoise (2006). Bhutan Himalayan Mountains Kingdom (5th ed.). Odyssey Books and Guides. pp. 136–137. ISBN978-962-217-810-vi.

- ^ "Tibetan monks: A controlled life". BBC News. twenty March 2008.

- ^ "Himalayan Forests Disappearing". Earth Island Periodical. 21 (4): 7–8. 2006.

- ^ Mishra, Arabinda; Appadurai, Arivudai Nambi; Choudhury, Dhrupad; Regmi, Bimal Raj; Kelkar, Ulka; Alam, Mozaharul; Chaudhary, Pashupati; Mu, Seinn Seinn; Ahmed, Ahsan Uddin; Lotia, Hina; Fu, Chao; Namgyel, Thinley; Sharma, Upasna (5 Jan 2019). "Adaptation to Climatic change in the Hindu Kush Himalaya: Stronger Activeness Urgently Needed". The Hindu Kush Himalaya Cess: Mountains, Climate Change, Sustainability and People. pp. 457–490. doi:ten.1007/978-three-319-92288-1_13.

- ^ a b c Roy, Joyashree; Moors, Boil; Murthy, Thou. S. R.; Prabhakar, V. R. K.; Khattak, Bahadar Nawab; Shi, Peili; Huggel, Christian; Chitale, Vishwas (5 Jan 2019). "Exploring Futures of the Hindu Kush Himalaya: Scenarios and Pathways". The Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment: Mountains, Climate Change, Sustainability and People. pp. 99–125. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-92288-1_4.

Sources [edit]

Full general [edit]

- Wester, Philippus; Mishra, Arabinda; Mukherji, Aditi; Shrestha, Arun Bhakta, eds. (2019), The Hindu Kush Himalya Assessment: Mountains, Climate Change, Sustainability and People, Springer Open, ICIMOD, HIMAP, ISBN978-3-319-92287-4, LCCN 2018954855

- Zurick, David; Pacheco, Julsun (2006), Illustrated Atlas of the Himalayas, with Basanta Shrestha and Birendra Bajracharya, Lexington: University Printing of Kentucky, ISBN9780813123882, OCLC 1102237054

Geology [edit]

- Chakrabarti, B. K. (2016). Geology of the Himalayan Belt: Deformation, Metamorphism, Stratigraphy. Amsterdam and Boston: Elsevier. ISBN978-0-12-802021-0.

- Davies, Geoffrey F. (2022). Stories from the Deep Earth: How Scientists Figured Out What Drives Tectonic Plates and Mountain Building. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-91359-5. ISBN978-3-030-91358-8.

- Frisch, Wolfgang; Meschede, Martin; Blakey, Ronald (2011). Plate Tectonics: Continental Drift and Mount Building. Heidelberg: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-iii-540-76504-2. ISBN978-three-540-76503-five.

Climate [edit]

- Clift, Peter D.; Plumb, R. Alan (2008), The Asian Monsoon: Causes, History and Effects, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN978-0-521-84799-5

- Barry, Roger E (2008), Mountain Weather condition and Climate (3rd ed.), Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Printing, ISBN978-0-521-86295-0

Environmental [edit]

Society [edit]

Pilgrimage and Tourism [edit]

- Bleie, Tone (2003), "Pilgrim Tourism in the Primal Himalayas: The Case of Manakamana Temple in Gorkha, Nepal", Mountain Research and Development, International Mount Order, 23 (2): 177–184, doi:x.1659/0276-4741(2003)023[0177:PTITCH]two.0.CO;2, S2CID 56120507

- Howard, Christopher A (2016), Mobile Lifeworlds: An Ethnography of Tourism and Pilgrimage in the Himalayas, New York: Routledge, doi:10.4324/9781315622026, ISBN9780367877989

- Humbert-Droz, Blaise (2017), "Impacts of Tourism and Military Presence on Wetlands and Their Avifauna in the Himalayas", in Prins, Herbert H. T.; Namgail, Tsewang (eds.), Bird Migration beyond the Himalayas Wetland Performance amid Mountains and Glaciers, Foreword by H.H. The Dali Lama, Cambridge, Great britain: Cambridge University Press, pp. 343–358, ISBN978-1-107-11471-v

- Lim, Francis Khek Ghee (2007), "Hotels as sites of power: tourism, condition, and politics in Nepal Himalaya", Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, New Series, Imperial Anthropological Institute, 13 (3): 721–738, doi:10.1111/j.1467-9655.2007.00452.10

- Nyaupane, Gyan P.; Chhetri, Netra (2009), "Vulnerability to Climate Change of Nature-Based Tourism in the Nepalese Himalayas", Tourism Geographies, eleven (i): 95–119, doi:10.1080/14616680802643359, S2CID 55042146

- Nyaupane, Gyan P.; Timothy, Dallen J., eds. (2022), Tourism and Development in the Himalya: Social, Environmental, and Economic Forces, Routledge Cultural Heritage and Tourism Serial, London and New York: Routledge, ISBN9780367466275

- Pati, Vishwambhar Prasad (2020), Sustainable Tourism Development in the Himalya: Constraints and Prospects, Environmental Scientific discipline and Applied science, Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-58854-0, ISBN978-3-030-58853-3, S2CID 229256111

- Serenari, Christopher; Leung, Yu-Fai; Attarian, Aram; Franck, Chris (2012), "Agreement environmentally significant beliefs among whitewater rafting and trekking guides in the Garhwal Himalaya, India", Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 20 (five): 757–772, doi:10.1080/09669582.2011.638383, S2CID 153859477

Mountaineering and Trekking [edit]

Further reading [edit]

- Aitken, Nib, Footloose in the Himalaya, Delhi, Permanent Black, 2003. ISBN 81-7824-052-1

- Berreman, Gerald Duane, Hindus of the Himalayas: Ethnography and Change, 2nd rev. ed., Delhi, Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Edmundson, Henry, Tales from the Himalaya, Vajra Books, Kathmandu, 2019. ISBN 978-9937-9330-3-ii

- Everest, the IMAX movie (1998). ISBN 0-7888-1493-1

- Fisher, James F., Sherpas: Reflections on Change in Himalayan Nepal, 1990. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1990. ISBN 0-520-06941-ii

- Gansser, Augusto, Gruschke, Andreas, Olschak, Blanche C., Himalayas. Growing Mountains, Living Myths, Migrating Peoples, New York, Oxford: Facts On File, 1987. ISBN 0-8160-1994-0 and New Delhi: Bookwise, 1987.

- Gupta, Raj Kumar, Bibliography of the Himalayas, Gurgaon, Indian Documentation Service, 1981

- Hunt, John, Rising of Everest, London, Hodder & Stoughton, 1956. ISBN 0-89886-361-9

- Isserman, Maurice and Weaver, Stewart, Fallen Giants: The History of Himalayan Mountaineering from the Age of Empire to the Historic period of Extremes. Yale University Printing, 2008. ISBN 978-0-300-11501-7

- Ives, Jack D. and Messerli, Bruno, The Himalayan Dilemma: Reconciling Development and Conservation. London / New York, Routledge, 1989. ISBN 0-415-01157-4

- Lall, J.S. (ed.) in association with Moddie, A.D., The Himalaya, Aspects of Alter. Delhi, Oxford Academy Printing, 1981. ISBN 0-xix-561254-X

- Nandy, S.Northward., Dhyani, P.P. and Samal, P.Yard., Resources Information Database of the Indian Himalaya, Almora, GBPIHED, 2006.

- Swami Sundaranand, Himalaya: Through the Lens of a Sadhu. Published by Tapovan Kuti Prakashan (2001). ISBN 81-901326-0-1

- Swami Tapovan Maharaj, Wanderings in the Himalayas, English Edition, Madras, Chinmaya Publication Trust, 1960. Translated by T.N. Kesava Pillai.

- Tilman, H. W., Mount Everest, 1938, Cambridge Academy Press, 1948.

- Turner, Bethan, et al. Seismicity of the Earth 1900–2010: Himalaya and Vicinity. Denver, The states Geological Survey, 2013.

External links [edit]

- The Digital Himalaya inquiry project at Cambridge and Yale (archived)

- Geology of the Himalayan mountains

- Nascency of the Himalaya

- S Asia's Troubled Waters Journalistic project at the Pulitzer Centre for Crunch Reporting (archived)

- Biological diversity in the Himalayas Encyclopedia of Earth

Himalayas Mountains On A Map,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Himalayas

Posted by: becerrawituare.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Himalayas Mountains On A Map"

Post a Comment